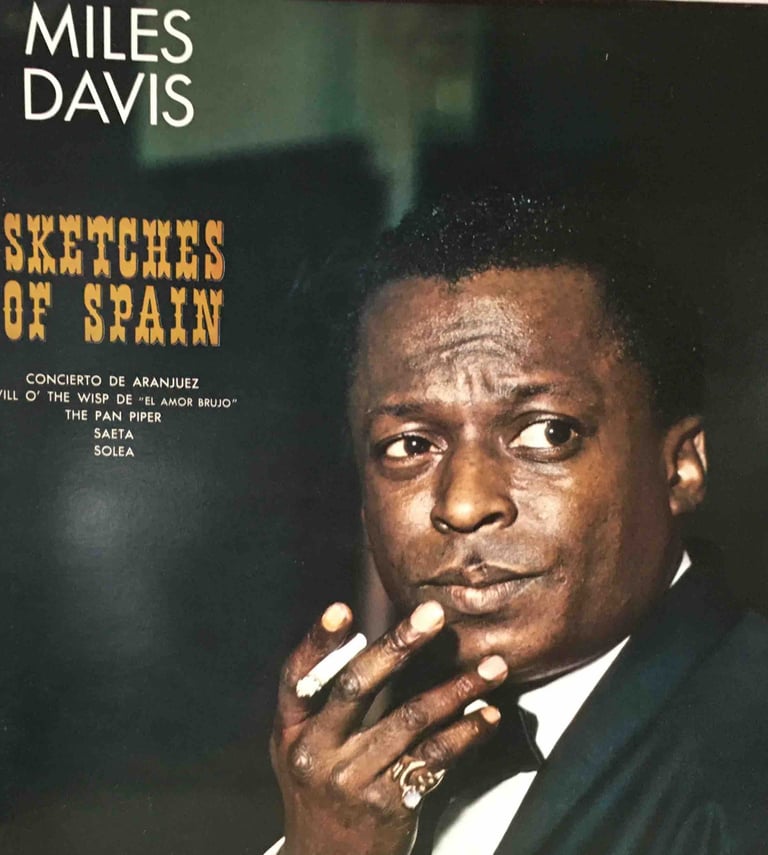

From the Crate #4 Miles Davis 'Sketches of Spain'

In which I review old albums from a 3 crate vinyl haul in 2021. #4 Review of Miles Davis' 'Sketches of Spain'

HIGH PLAINS DRIFTER

A review of Miles Davis' Sketches of Spain

(A quick note on the cover, for the aficionados. I am aware this isn't the iconic cover. The album I picked up in my crate haul is a European release, this particular pressing from Holland)

My first thoughts in preparing to write this review: what is Miles Davis and who is he to the general public? What is his legacy? He is a household name, surely, but who really knows his music (outside the jazz listening world) and is he still important? Reading forums rating his best albums there are always multiple questions in the comment sections: where do I start with Miles Davis? Where is the gateway? As with an approach to any jazz great, or any type of jazz, this is a really crucial question. When I started listening to jazz I was directed (via a jazz history book) towards Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and the Bebop movement. For me, this was exactly the wrong place to start. I found it difficult to listen to and, frankly, unpleasant. It put me off jazz for several years and left me feeling, as I believe many initiates do, that I was stupid and unable to comprehend the apparent complexity of it all. What am I missing? Why am I not enjoying this? But I have come a long way along the jazz road since then. I’ve learned, of all the branches of music out there, perhaps jazz has the widest variety and scope – there are numerous places one can begin one’s jazz journey.

The reason I bring this up is because I ask myself: despite it not being my favourite Miles Davis album (probably not in my top 5 if I’m honest – but that’s for another blog) is Sketches of Spain Miles Davis’ most accessible album? It’s classical European leanings (in particular its obvious Spanish influence) combined with the maestro’s floating trumpet (a worthy subject on its own; suffice to say, Miles plays with space and ease like no one else) along with the obvious cinematic drama, these elements make Sketches an album of music both instantly recognizable and yet still distinctly, if only instrumentally, jazz.

It became clear during the fifties that Miles Davis had gravitated towards Europe and its varied culture. This became, slowly but surely, evident in his music. Apparently it was flamenco that caught his interest towards the end of the decade (‘59 & ‘60). When he heard the composition Concierto de Aranjuez (which not surprisingly has guitar as its principal instrument) he was moved enough to share the record with his great collaborator of the time, Gil Evans (a man as integral to this album as Miles himself). It was then they decided to do an album in a type of Spanish folk tradition. Most of the tracks on Sketches of Spain are traditional Spanish songs arranged by Gil Evans. Only Solea (which I have to confess is my favourite track) is an original arrangement by Evans. And so the album, an ambitious early fusion (one of what would be many in Miles Davis’ career) has a sound that evokes wonderful images of sweeping Andalucían hills and at the same time endless flat dry-grass border plains, which Miles Davis’ trumpet soars over like a solitary eagle.

This album, if nothing else, is a sumptuous example of Miles Davis as an accomplished, fully-realized, experimental musician. In my opinion, there are few better examples of what Miles and his trumpet are all about. It’s got to do with the timing, the space for drama, and the deep imagery one can’t help but get lost in. Miles paints with his trumpet. He doesn’t fill up a joyful party like Lois Armstrong. He doesn’t attempt to wow you with instrumental gymnastics like Dizzy Gillespie. No, Miles uses his trumpet to take you into flight. He shows you what he is seeing: the bird’s eye view. He blows in a way that communicates complex emotions with an easy high-plains drifting, and all with the mildest of traditional swing.

There is something to be said about this music being dated. I accept that. You’re unlikely to hear anything like it released these days. As I suggested earlier, there is a cinematic feel, and even a dance-like quality to much of the music. (This seems obvious when referencing influences like flamenco.) In fact, it doesn’t seem out of place to say that West Side Story (my favourite, if dated, musical of all time) doesn’t seem so far removed from what one hears on Sketches of Spain. I am not suggesting the music is coming from precisely the same source, but merely that it comes from a similar time (West side story, the film, was released in 1961) and uses similar drama-laced themes: Latin influence, classical ballet mixed in tentatively with a finger-clicking hipness most associated with the jazz of the time. In my opinion (the purists will be calling blasphemy here) not a stretch at all to regard these two works of art as 'thematically' contemporary.

Delving into the tracks, starting with Concierto de Aranjuez. This is the track, above all others, where I got the curious sensation we could easily be listening to a movie soundtrack – a western perhaps (a twisted spin on something akin to Morricone). The track opens slowly and after several minutes pulsates into a very mild, barely-decipherable swing, underlined by the unending click of rattlesnake castanets. The tone is moody, brooding and I come back to that feeling of open space (the Cormac McCarthy cowboy on open border plains). And all the while the music holds us with a growing tension. When it does finally break into a dramatic sweeping-hand reveal, waking us out of our reverie, it is only fleeting. It’s almost as if the cowboy has seen something, something on the horizon to alarm him, but then quickly realizes it isn’t, in fact, anything of consequence. He can go back to his clip-clop riding, and his hat-shaded brooding. So we are brought back to a state of waiting, perhaps even a state of longing.

Concierto de Aranjuez isn’t easy to decipher. Distinctly Spanish in signature, yet Miles keeps offering us a different, previously unseen outlook with his instrument. Again, the eagle watching the cowboy, watching the plains. The rider click-clacks on, suggesting the ride will never end. As the track’s name suggests there is the structure of something more classical going on here. The European-ness of this record is most evident on this track. Miles is stretching his muscles into areas he has no background in. But he does it with an ease, with aplomb. There is no doubt that Davis is at the top of his game here. He isn’t so much trying to be Spanish, but building a bridge between his understanding of music, and the inheritance of long European tradition. As with all fusion (and I doubt this was a word they used to describe this music) it asks us to listen with different hats. Not everyone pulls this off, but Miles Davis does. And he will do it repeatedly throughout his career. His ability to change, to experiment, to create with such spontaneity and beauty, these are the reasons we can offer him up as one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century (if not of all time). Subjective gobbledygook, I know, but what is opinion without hyperbole and hubris?

So excuse me for skipping certain tracks. To these ears, the themes that follow Concierto de Aranjuez continue in the same vein, offering up slightly different landscapes (perhaps a desert valley, the passing through of a small western town) always holding true to wide-open landscapes. The drama is ever present, the music is driving and pleasant and, as I’ve already alluded to, Miles Davis plays like a dream. Saeta offers up a last post, New-Orleans-inflected march, and then goes into Miles soloing over the faint sounds of recurring drums. More brooding. More plaintive cries. And just when you think the eagle is about to wilt and die, the band starts to kick in, like a band of angels, and the whole thing takes on a drunken, reckless joyousness. It’s like the Calvary have been called in, last minute, and victory is imminent. Miles Davis’s trumpet takes us to the brink, but Evan’s arrangement just can’t help itself – it has to save the day.

But the track I truly love the most on this record is the last track, Solea. It encompasses everything that the album has achieved hitherto, but its arrangement swings far more, and, after the initial ‘thematic’ opening, Miles is let off the leash a little. There’s a greater sense of jazz to this number than all the preceding tracks, and you wouldn’t be hard pressed to find this track on Kind of Blue or, more likely, on one of the other brilliant Evans / Davis collaborations.

Solea finishes off a body of work in which, even if you don’t like it, it’s difficult to escape the truth: that these men had a vision and they accomplished exactly what they set out to do. For me this is the definition of high-end art. Sketches is an album that begins (along with other seminal recordings) to redefine an art-form that had, as its origin, a freeform built on swinging improvisation. But as the artists were ever increasingly recorded, and listening to records became the primary source for consuming music, composition became ever more important. And it seems to me, this monumental moment in time is where Miles Davis found himself. What I love about Miles Davis, above all other jazz musicians (and I have many favourites) is that he is a man rooted in composition. He serves the song, so to speak. Even if he is composing on the spot, improvising in the studio, it is still ultimately a rendering of composition. Music being written in the now, but nevertheless, being written. And another thing about Miles: as he got older and grew in stature – he never tried to show off and was generous in the sharing of composition. It’s not an exaggeration to argue that Coltrane might never have been the Coltrane we all know and love without his blossoming under Davis.

Its impossible not to look at Davis’ body of work at the time Milestones, Porgy & Bess and Kind of Blue: obviously some of the greatest jazz records of all time. He seemed to oscillate, for some time, between collaborating with Gil Evans (as he did on this record) and working with his incredible group (Coltrane, Bill Evans etc). And while I lean on the ‘group’ a little more for my usual jazz fix, I still love records like Sketches. Historically speaking, his collaborations with Gil Evans have a strong place in jazz history. Perhaps these collaborations ushered in a whole new concept of ‘arrangement’ in jazz – a new intricate, anything-goes fusion. Theoretically, once the ‘cultural’ door was kicked down (and there are arguments to be had about who kicked it down) jazz would never be the same. So this brings me back to my opening questions, all surrounding the importance of Miles Davis. Is he relevant? Is he important? I’m drawn to the idea of making an end-all statement here, but the truth is, not everyone listens to jazz, and not everyone likes it or wants to even try to like it. What I do know, and am capable of knowing, is wholly subjective: that the sound of Miles Davis’ trumpet is one of the most beautiful sounds I have ever heard. I really don’t believe there is anything in music quite like it. I can’t even begin to describe how it makes me feel. And his body of work is so extensive, so varied, that I do believe there is something in there for everyone. But if you want to find it, you’re going to have to explore. And, to conclude this little piece of blah, Sketches of Spain is not a bad place to start. Not a bad place at all.