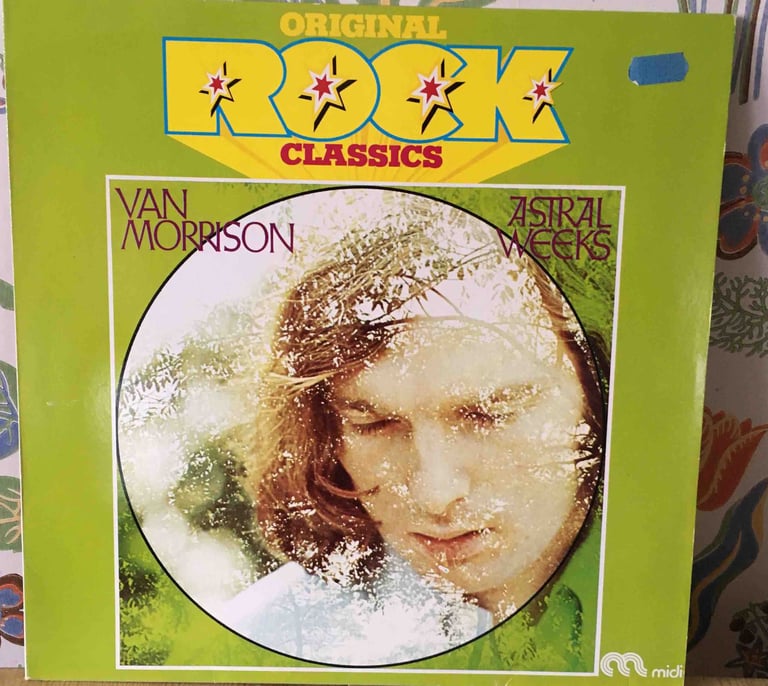

From the Crate #5 'Astral Weeks' by Van Morrison

In which I review old albums from a 3 crate vinyl haul in 2021. #5 Review of Van Morrison's 'Astral Weeks'

ROSE TINTED SUNGLASSES - Astral Weeks – the home of Van Morrison

Are places branded by their recent history? Afghanistan was once – and not so long ago – a relatively liberal and progressive society that is now branded by violence, misogyny and all the trappings of extreme, militant theism. It is impossible to hear the word ‘Afghanistan’ and not think of oppression, darkness and bloody murder. It’s almost as if the once fairytale-like country never existed before the Soviet occupation and the successive, interminable wars. In marketing terms, this would be ultimate branding.

There is no doubt the Belfast of Astral Weeks has more than a hint of rose tinted glasses on it. When Van Morrison sings of Belfast (which he does surprisingly often) it’s a Belfast pre-Troubles. It’s the Belfast of his youth – ‘in the days before Rock ‘n Roll’. In the beautiful, meandering, spoken-word chant On Hyndford Street (from Hymns to the Silence, 1990) Morrison is unapologetic about his sentimentality and it works beautifully: ‘On sunny summer afternoons; Picking apples from the side of the tracks; That spilled over from the gardens of the houses on Cyprus Avenue; Watching the moth catcher working the floodlights in the evenings; And meeting down by the pylons’. He tells us of the Belfast of his youth, and the romanticizing rings true, I think, for all of us, no matter where we grew up. Perhaps the beauty of On Hyndford Street is that we all romanticize our youths. We all recall with rose tinted sunglasses.

Astral Weeks was written before the Troubles escalated into twenty or so years of bloody violence – between two divisions of the same strand of theism – that the world watched on their daily news, in awe, sorrow, and utter bewilderment. It was a ‘war’ that put Belfast on a map that it surely never wanted to be on. It branded the city, and for anyone my age or older, it still sends a shudder down the spine. But the Van Morrison of Astral Weeks seems oblivious – as a child should be – of the divisions growing in his city. He sees wonder in the smallest of things. It’s a world where ordinary streets like Cyprus avenue take on a magic quality, and the numerous hiding places and landmarks (Down in the hollow; walking by the railroad; the avenue of trees; in the backstreet; over Beechie river; saw you there in Orangefield) are relatable to anyone with an imaginative childhood. This Belfast is, above all, a peaceful place.

When Morrison was writing this album, he wasn’t living in Belfast. He was far away in Boston and New York with ambitions of taking his solo career – after a relatively successful stint with the band Them and a hit with Brown Eyed Girl – to a more artistic, conceptual place. Perhaps he felt at the time he was leaving Belfast forever when he wrote these songs, thus the childhood imagery, the memories of fun he seems to now long for, but he knows is irretrievable. Perhaps this was his way of leaving behind a place, but also his youth, his innocence. It’s hard to say, as he employs streams of imagery, rather than any type of poetic narrative. He is at once painting concise pictures, but not offering anything particularly cohesive. It’s a dream. Morrison has said this album isn’t autobiographical, but surely it is some type of self-portrait, or a series of such. Where else but within him do the vivid images and wistful longings come from?

The opening title track sets a flowing preachy tone that arguably not only sets out a sonic staple for this record, but also for Van Morrison’s whole career. With a repetitive, rhythmic surge, Van’s inflections all come through his white-soul voice and how he bends and stretches it – while the rhythm holds true. Lyrically there are themes that, in retrospect, seem very Van: ‘If I ventured in the slipstream; Between the viaducts of your dream’. Water, as a spiritual landscape, seems to feature heavily, as does the Christian-like insistence: ‘to be born again’. Anyone who has listened to Van extensively knows that spirituality is imbued all throughout his work. As Astral Weeks, the song, pulses forward it eventually starts to slow and become quiet, as Morrison tones everything down with his whispering secret-sharing voice. I can’t escape the idea he is merely a little boy, whispering in his friends ear, something he feels is life-defining, something about God, or words from beyond. Childish fantasy. ‘Way up in Heaven’ and ‘In another time; another place.’ Van Morrison grips you with his sense of drama. He holds you. And he isn’t about to let you go.

What is Van Morrison? This short, chubby man from Northern Ireland who sings like a black soul singer and preaches like a southern Baptist. How is it so? I can’t think of anyone that embodies the mystery that music is like Van Morrison. It’s almost as if he shouldn’t be, that it shouldn’t have played out this way. But there is no doubting that the man reeks of authenticity. He sings from the soul and what he presents is the purest form of self-expression. I’m often swept off my feet by what he does. And I’m never bored. There’s the Van that can console you after a break up; the Van that you can dance to or sing along to on a drunken Saturday afternoon; and then the Van that takes you on a spiritual journey where only angels dare to go.

Sweet Thing has been my favorite Van Morrison song, since the first time I heard it. The rhythmic flow takes off and quickly sucks you into its growing intensity. It’s beautifully acoustic, with strings swirling in and out. The double bass, Richard Davis’ mastery, elevates this track to stratospheric dimensions. Again we’ve got water ‘blue oceans’ and ‘ferry boats’ and ‘gardens misty wet with rain’. There’s a youthful playfulness to Sweet Thing, like a young boy with a secret crush on a girl who sits across the classroom. Van is desperate to tell her, to read her poetry under a tree, to lie on his back with her and count the stars. But you also get the feeling that he will never get that girl. What an aptly descriptive word that is – ‘crush’.

Cyprus avenue, the street, isn’t so far from where Van Morrison grew up on Hyndford street. I imagine it’s a tree-lined upperclass street, with big houses and sweeping lawns, and that young Morrison used to walk down it, coming home from school. That it perhaps held a sense of aspiration for Morrison – the idea that people had it better than him, that people were living another life there, an elevated life, a better life. All speculation, I admit. The song itself Cyprus Avenue is full of wonderful imagery: ‘leaves fall one by one; my tongue gets tied; walking with my cherry wine; ribbons in her hair; the sun shone through the trees’. Again, we’re left with the jilted school boy, taking in a much bigger world, and longing for the girls, or perhaps even the same girl alluded to in Sweet Thing. As said, its all speculative, because Van presents us image, rather than story.

People often refer to The Way Young Lovers Do as the weakest track on an otherwise masterpiece. I disagree. I love the pace of the song, the cinematic montage-like drama to it, and the subtle leanings towards big band jazz. The song is Van Morrison all over.

And then comes the hypnotic Madame George. What a song! And… what the fuck is it about? Who is it about? So I want to approach this on face value. I know there are various things Morrison has said over the years, and lots of online speculation about the meaning of this song, but let's look at it, let's take it in on face value, as, perhaps, it was meant to be taken in. The very name ‘Madame George’ evokes transgender dreams of an ageing drag queen, performing for the drunks down at ‘Ford and Fitzroy’ (streets, I imagine, though I am happy to be corrected). Given that this song was written in the sixties, it seems quite progressive or even beatnik, rather than hippy. I see dark Hubert Selby Jr alleyways. The curious schoolboy has grown up now, perhaps, he has seen some enlightening, forbidden, grown-up things, but he still likes to ‘hop on the train’ and ‘throw pennies at the bridges’. Okay, it’s impossible to decipher this song from the lyrics alone, but if we are to buy into this character Madame George, we can also see her as someone we love, someone we must grow out of, say goodbye to, and someone, who, perhaps we feel sadness for. Again, the name Madame George does thrust forward images of identity and conflicting wills. It’s hard to see this character as anything other than a gritty-part-of-town outsider. And we are prompted to ‘say goodbye to Madame George’ – why? Perhaps we aren’t a part of that equation? Perhaps we’re too straight? Perhaps we’re merely getting a glimpse of the clown without make-up, the behind the scenes machinations, the dirty caravans and the outcast freaks. The circus isn’t as magical as we once thought. The truth of life is darkness. We’re reaching here; we’re reaching because Morrison demands it with teasing abstract magician tricks.

The three tracks I haven’t mentioned yet are all wonderful in their own right. Beside You again has rain filled windows and more child-like longing for a beautiful girl or woman, just beyond the singer’s reach. Ditto, the sleepy Ballerina: ‘And this time I forget to slip into your slumber; The light is on the left side of your head.’ And lastly Slim Slow Slider, a song that has a fairytale-like lightness, until we realize that the figure of the narrator’s fixation is in fact with another man: ‘And I know you won’t be back.’ Perhaps, just perhaps, this figure is not a woman at all? Perhaps it is the Belfast of Van’s youth? Perhaps, and more likely, we will never know.

I don’t need to point out that Astral Weeks is a classic. I don’t need to tell anyone reading this how beautiful, mystical and enchanting this record is. It is often rated in top tens (of all-time best lists). There will be those that will argue there are better Van Morrison albums, and that could be true, but I would say this: that this is the one Van Morrison record where you really feel that Morrison is fully present, whether that be through the eyes of a child, or the teenager, full of longing, or the sentimental adult – they walk the Belfast streets together, hand in hand: ‘skipping stones and listening to transistor radios’. There is something about this album that feels fully realized. I am not sure Van Morrison was setting out to do something conceptually, but you get the feeling that his headspace was clear and concise, he knew what he wanted (or maybe what he didn’t want) and whatever came out of that brain had a tone and theme that was consistent and whole.